December 25, 2015

Adventists in American Courts—The Sunday Law Cases

11 January 2013 | Julius Nam

Beginning in the late 1870s, state Sunday laws in the U.S.—which had long been unenforced—received renewed attention and execution. After failing to get a national Sunday law passed in Congress, the National Reform Association (a coalition of Christian abolitionists, temperance promoters, and morality advocates seeking to prevent further secularization of American society and advance public morality based on Christianity) successfully led a campaign in Pennsylvania in 1879 for the passage of an expanded and strengthened Sunday law—as well as for the defeat of an exemption clause for Saturday observers. Leading the counter-campaign against Sunday laws were liberals, including liquor industry reps whose business was significantly impacted by Sunday laws.

Beginning in the late 1870s, state Sunday laws in the U.S.—which had long been unenforced—received renewed attention and execution. After failing to get a national Sunday law passed in Congress, the National Reform Association (a coalition of Christian abolitionists, temperance promoters, and morality advocates seeking to prevent further secularization of American society and advance public morality based on Christianity) successfully led a campaign in Pennsylvania in 1879 for the passage of an expanded and strengthened Sunday law—as well as for the defeat of an exemption clause for Saturday observers. Leading the counter-campaign against Sunday laws were liberals, including liquor industry reps whose business was significantly impacted by Sunday laws.

The two sides clashed in California after a Mr. Koser, a saloon owner, was arrested in November 1881 for violating California’s Penal Code § 300, which exacted fines to those who opened on Sunday “any store, workshop, bar, saloon, banking-house or other place of business for the purpose of transacting business therein.” After his arrest, Koser filed a habeas corpus petition to the Supreme Court of California, challenging the legitimacy of the statute under the state constitution. A key argument by Koser was that the statute represented an impermissible religious regulation. The state’s main argument was that the Sunday law was only a public welfare statute, which the state had the right to enact. In March 1882, the Court, in a 4-3 decision, held that the law was constitutional.

This legal battle provided the backdrop to (Ellen White’s son) W. C. White’s arrest in the same year for violating the same statute by operating the Pacific Press (in Oakland, California) on Sundays.* In response to prosecutions such as this and the Republican Party’s support of the Sunday law, Adventists in California deserted the GOP en masse and voted for Democrats who fought against Sunday laws in the state’s general election in November 1882. The Democrats won every major state office in that election, gained control of the state legislature, and repealed the controversial Sunday statute in 1883.

Scoles v. State (1886)

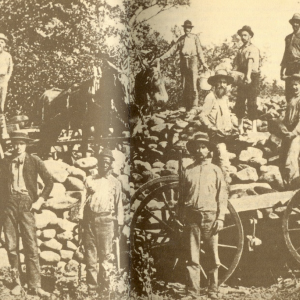

Unlike in California, in many Southern states, new Sunday laws were enacted and existing Sunday laws strengthened with unwelcome consequences for many Adventists. The first legal opinion involving a Seventh-day Adventist criminalized by a Sunday statute appears to be the Arkansas Supreme Court’s decision in Scoles v. State, 1 S.W. 769 (Ark. 1886). In that case, five Adventists, including James W. Scoles, a minister, were arrested for violating the state’s Sunday law in the spring of 1885, after a neighbor testified to the Washington County grand jury six months later that he knew of Seventh-day Adventists who work on Sundays. The state’s Sunday law criminalized “laboring and performing other services” that were more than “customary household duty, of daily necessity, comfort, or charity.” The criminal act in question was painting the exterior of their church building on Sunday, May 3, 1885.

The Arkansas state law under which the Adventists were arrested was the Revised Statutes of 1838, which until 1884 contained the following clause: “Persons who are members of any religious society, who observe as Sabbath any other day of the week than the Christian Sabbath or Sunday, shall not be subject to the penalty of this act, so that they observe one day in seven agreeably to the faith and practice of their church or society.” But on March 3, 1885, the state legislature removed this exception, and Scoles and his parishioners appear to have been among the first to be arrested under the exception-less Sunday statute.

In re King (1891)

Tennessee was another state in which Adventists found themselves prosecuted for Sunday law violations. Several Review and Herald issues in 1886 report on the case involving three Adventists indicted for Sunday labor in Tennessee—W. H. Parker, James Stem, and William Dortch. Apparently, their case also reached the supreme court of their state. But their convictions were summarily affirmed without an opinion. Like Adventists in Arkansas, rather than pay fines, they served time in jail to protest the law.

The first Tennessee case yielding a judicial opinion was In re King, 46 F. 905 (C.C. Tenn. 1891), which was also the first-ever federal opinion of any kind involving a Seventh-day Adventist. In that case, R. M. King, an Adventist farmer in Obion County, was charged with common law nuisance for working his field in violation of the state’s stringent Sunday law (which also did not have an exception for Saturday observers). Initially, King chose to pay $3 fines each time he was cited and kept working on Sundays. Annoyed, his neighbors got him indicted on the more serious charge of common nuisance, which came with a $75 fine and jail time until the fine was paid in full.

Proliferation of Sunday Law Prosecutions

Helped by decisions such as Scoles and King, Sunday law prosecutions flourished in Arkansas, Tennessee, and many parts of the United States. As one website notes, Scoles was the first of at least twenty-one Sunday law prosecution cases in Arkansas alone in the late 1880s. Almost all of the defendants appear to have been Adventists. Many more Adventists in Tennessee were convicted of Sunday law violations, placed in chain gangs and subjected to hard labor. One early 20th century author counted “over one-hundred Seventh-day Adventists in the United States and about thirty in foreign countries [who were] prosecuted for quiet work performed on the first day of the week, resulting in fines and costs amounting to $2,269.69, and imprisonments totaling 1,438 days, and 455 days served in chain gangs” (2).

A survey of legal opinions issued since Scoles and King shows that Sunday law prosecutions of Seventh-day Adventists persisted well into the 20th century, despite continuing constitutional objections raised by Adventists. After Scoles and King, at least twelve additional opinions involving Adventists were issued between 1894 and 1963 by courts in Illinois, Kansas, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Washington.

Click on Link:

http://spectrummagazine.org/article/julius-nam/2013/01/11/adventists-american-courts%E2%80%94-sunday-law-cases